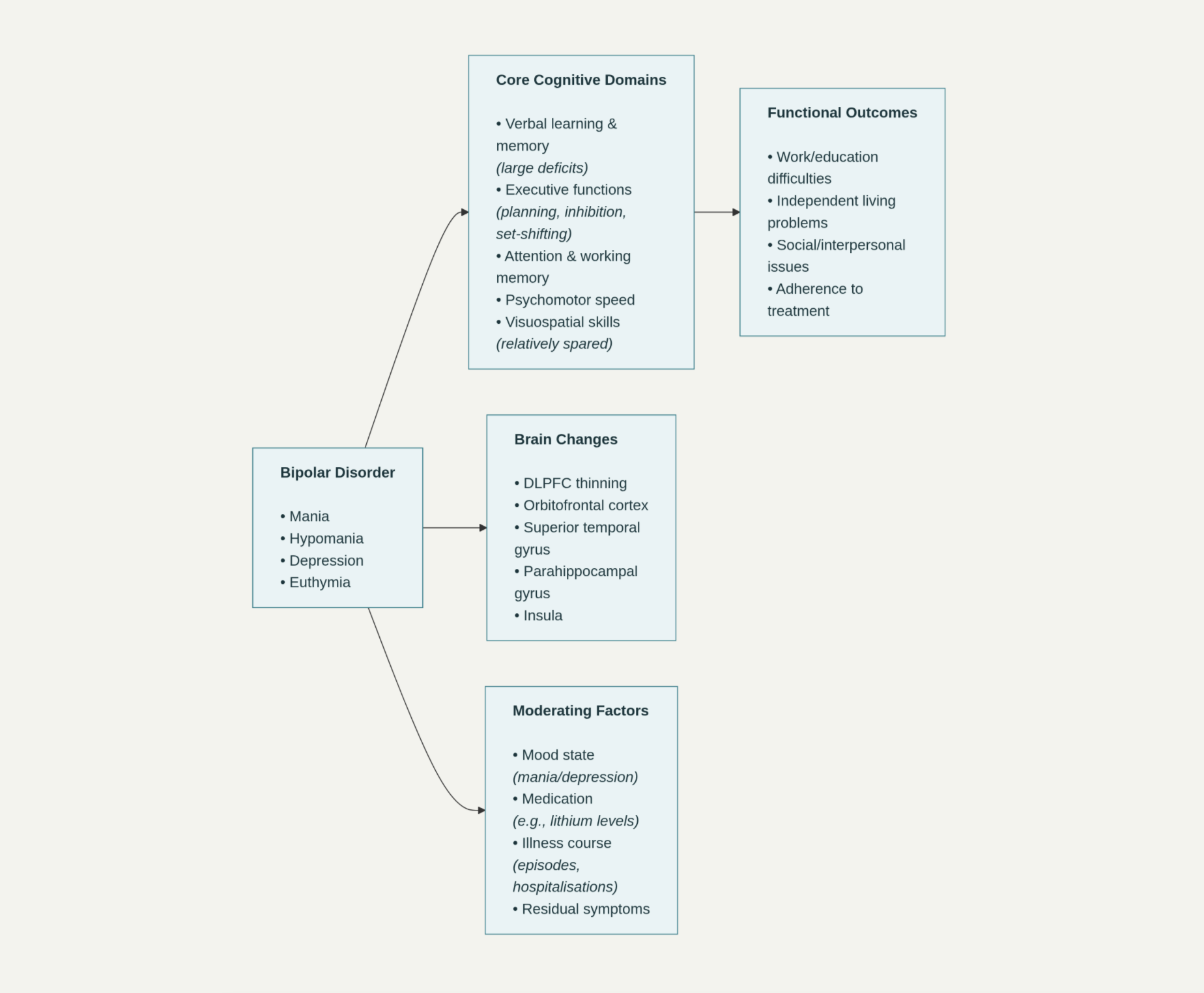

Bipolar Disorder (BD) is a severe and chronic psychiatric condition characterised by recurrent episodes of mania, hypomania, and depression, interspersed with periods of relative stability known as euthymia. Historically, the focus of research and clinical management has centred on the profound mood dysregulation that defines the illness. However, over the past two to three decades, a substantial body of evidence has illuminated a critical, yet often overlooked, dimension of BD: significant and pervasive cognitive dysfunction. This cognitive impairment is not merely a transient symptom of acute mood episodes but represents a core feature of the disorder, with profound implications for diagnosis, treatment, and long-term psychosocial outcomes. This essay synthesises evidence from meta-analytic reviews and contemporary neuroimaging studies to explore the profile, magnitude, and moderating influences of cognitive impairment in BD, arguing that it constitutes a fundamental and debilitating aspect of the illness that persists across all clinical states.

The Profile and Magnitude of Cognitive Deficits in Euthymia

A pivotal insight from modern neuropsychology is that cognitive dysfunction in BD endures well beyond the resolution of acute affective symptoms. Meta-analytic investigations of euthymic patients—those in a state of clinical remission—consistently demonstrate a generalised pattern of moderate-to-large impairments across nearly all major cognitive domains (Kurtz & Gerraty, 2009). This widespread deficit challenges earlier notions that cognitive issues were purely state-dependent consequences of mood disturbance.

The most pronounced deficits are observed in verbal learning and memory. Kurtz and Gerraty’s (2009) meta-analysis found large effect-size impairments (d = .81) on tests like the Rey Auditory Verbal Learning Test (RAVLT) and the California Verbal Learning Test (CVLT). Similarly, delayed recall of both verbal and non-verbal information shows substantial deficits (d = .80-.92), indicating significant challenges in the consolidation and retrieval of new information. Executive functions—the higher-order cognitive processes responsible for planning, problem-solving, cognitive flexibility, and inhibitory control—are also markedly impaired. Measures such as the Stroop Colour-Word Test (interference condition; d = .75) and Trail Making Test Part B (d = .73) reveal significant difficulties with set-shifting, response inhibition, and processing efficiency (Kurtz & Gerraty, 2009).

Furthermore, impairments extend to other domains. Attention, particularly sustained visual vigilance as measured by Continuous Performance Tests (d = .69), and working memory (e.g., Digits Backward; d = .65) are compromised. Psychomotor speed, assessed by tests like the Digit Symbol Substitution Test (d = .66), is also slower in euthymic BD patients compared to healthy controls (Kurtz & Gerraty, 2009). Interestingly, visuospatial constructional abilities, as measured by tasks like copying the Rey Complex Figure, appear relatively spared, showing only small effect-size impairments (Kurtz & Gerraty, 2009). This pattern of generalised impairment with particular vulnerabilities in verbal memory and executive control has been replicated in other major meta-analyses (Arts, Jabben, Krabbendam, & van Os, 2008; Bora, Yucel, & Pantelis, 2009; Robinson et al., 2006), solidifying its status as a reliable neuropsychological signature of the disorder.

Cognitive Impairment as a Trait Versus State Marker

A central question in BD research is whether cognitive deficits represent a stable trait (an enduring feature of the illness and a potential endophenotype) or are merely acute state effects that wax and wane with mood episodes. The consistent finding of impairment during euthymia strongly supports a trait-based model. For a cognitive deficit to be considered an endophenotype—a heritable, intermediate marker of illness liability—it must be present during remission and be evident in unaffected first-degree relatives at a higher rate than in the general population (Gottesman & Gould, 2003). The meta-analytic data on euthymic patients and studies showing attenuated deficits in relatives strongly satisfy these criteria (Arts et al., 2008; Bora et al., 2009).

However, clinical state undeniably exerts a moderating influence, exacerbating certain deficits. Kurtz and Gerraty’s (2009) comparative analysis revealed that patients in manic/mixed or depressed states show significantly greater impairment in verbal learning than their euthymic counterparts. The effect size for verbal learning ballooned to d = 1.43 during mania and d = 1.20 during depression, indicating a severe accentuation of this specific deficit during acute illness phases. Furthermore, the depressed phase was uniquely associated with a pronounced decline in phonemic fluency (Controlled Oral Word Association Test; d = .93), a finding not as exaggerated in mania (Kurtz & Gerraty, 2009). This suggests that while a baseline of cognitive impairment exists as a trait, the affective turmoil of acute episodes places additional, selective load on fronto-temporal circuits involved in memory encoding and verbal retrieval.

Image 1. Conceptual model of cognitive impairment in Bipolar Disorder and its functional impact

Moderating Factors: Medication, Illness Course, and Symptoms

The relationship between cognitive impairment, brain structure, and clinical presentation is complex and influenced by several confounding factors. A critical and often debated moderator is psychotropic medication. While some evidence suggests that medications like lithium and antipsychotics may have modest negative effects on psychomotor speed and memory, the bulk of research indicates that cognitive deficits are intrinsic to the illness. First-episode patients, often medication-naïve, show significant impairments, and unaffected relatives demonstrate similar, if milder, deficits without medication exposure (Kurtz & Gerraty, 2009). However, Degraff et al. (2023) found that higher serum levels of lithium were associated with worse cognitive performance in their sample, and mediation analyses suggested that both medication dosage and symptom severity (measured by the Young Mania Rating Scale) jointly influenced task outcomes. This highlights the difficulty in disentangling the effects of the illness from its treatment, but it does not negate the presence of a primary deficit.

The longitudinal course of the illness is another significant factor. While Kurtz and Gerraty’s (2009) meta-analysis did not find illness duration to be a strong moderator in cross-sectional data, other research supports a model of neuroprogression. Degraff et al. (2023) discuss that a greater number of affective episodes, hospitalisations, and longer illness duration are often linked to more severe cognitive decline and greater brain structural changes, such as white matter alterations and volume loss in the hippocampus and prefrontal cortex. This suggests that repeated mood episodes may have a “kindling” or toxic effect on the brain, leading to cumulative cognitive deterioration.

Furthermore, the definition of “euthymia” itself is a complicating factor. Many studies include patients with low-level residual depressive or manic symptoms, which can contaminate findings. Kurtz and Gerraty (2009) noted that controlling for such residual symptoms sometimes reduces the observed differences between patients and controls, implying that even sub-syndromal symptoms can impact cognitive performance. Therefore, what is often labelled as a “trait” impairment may still contain a subtle “state” component.

Psychosocial Impact and Treatment Implications

The clinical significance of cognitive impairment in BD cannot be overstated. It is strongly and independently associated with poor functional outcomes. Deficits in verbal memory and executive function predict difficulties in occupational attainment, independent living, social relationships, and the ability to adhere to treatment plans (Martinez-Aran et al., 2004). This functional disability often persists even when mood symptoms are well-controlled, leading to a significant gap between symptomatic recovery and functional recovery.

This reality necessitates a paradigm shift in treatment. Traditional pharmacotherapy, while essential for mood stabilisation, has shown limited efficacy in reversing cognitive deficits. As Degraff et al. (2023) conclude, their findings “underscore the need for cognitive remediation interventions.” Adjunctive psychosocial treatments, such as cognitive remediation therapy (CRT), which uses drill-and-practice and strategic coaching to improve cognitive skills, are emerging as vital components of a comprehensive treatment plan. Furthermore, the evidence for neuroprogression argues for early and effective intervention to stabilise mood and potentially mitigate the cumulative cognitive and neural damage associated with recurrent episodes.

Conclusion

In conclusion, cognitive impairment is a fundamental, pervasive, and disabling component of Bipolar Disorder. Evidence from meta-analyses reveals a robust profile of generalised deficits that persist during euthymia, with particular salience in verbal learning, memory, and executive functions, supporting its status as a core trait and potential endophenotype of the illness. Acute mood states selectively exacerbate these deficits, demonstrating an interaction between trait vulnerability and state burden. These cognitive findings are grounded in neurobiological reality, as seen in correlated patterns of cortical thinning in prefrontal, temporal, and limbic regions. While moderated by factors such as medication, symptom severity, and illness chronicity, the cognitive deficit is intrinsic and a primary driver of the poor psychosocial outcomes that characterise BD. Moving forward, recognising cognitive dysfunction as a therapeutic target in its own right is imperative. The future of BD management must integrate mood stabilisation with evidence-based cognitive and functional remediation strategies to bridge the gap between clinical recovery and a return to a meaningful quality of life.

References

Arts, B., Jabben, N., Krabbendam, L., & van Os, J. (2008). Meta-analyses of cognitive functioning in euthymic bipolar patients and their first-degree relatives. Psychological Medicine, 38(6), 771–785.

Bora, E., Yucel, M., & Pantelis, C. (2009). Cognitive endophenotypes of bipolar disorder: A meta-analysis of neuropsychological deficits in euthymic patients and their first-degree relatives. Journal of Affective Disorders, 113(1-3), 1–20.

Degraff, Z., Souza, G. S., Santos, N. A., Shoshina, I. I., Felisberti, F. M., Fernandes, T. P., & Sigurdsson, G. (2023). Brain atrophy and cognitive decline in bipolar disorder: Influence of medication use, symptomatology and illness duration. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 163, 421–429.

Gottesman, I. I., & Gould, T. D. (2003). The endophenotype strategy in psychiatry: Etymology and strategic intentions. American Journal of Psychiatry, 160(4), 636–645.

Kurtz, M. M., & Gerraty, R. T. (2009). A meta-analytic investigation of neurocognitive deficits in bipolar illness: Profile and effects of clinical state. Neuropsychology, 23(5), 551–562.

Martinez-Aran, A., Vieta, E., Reinares, M., Colom, F., Torrent, C., Sanchez-Moreno, J., Benabarre, A., Goikolea, J. M., Comes, M., & Salamero, M. (2004). Cognitive function across manic or hypomanic, depressed, and euthymic states in bipolar disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry, 161(2), 262–270.

Robinson, L. J., Thompson, J. M., Gallagher, P., Goswami, U., Young, A. H., Ferrier, I. N., & Moore, P. B. (2006). A meta-analysis of cognitive deficits in euthymic patients with bipolar disorder. Journal of Affective Disorders, 93(1-3), 105–115.