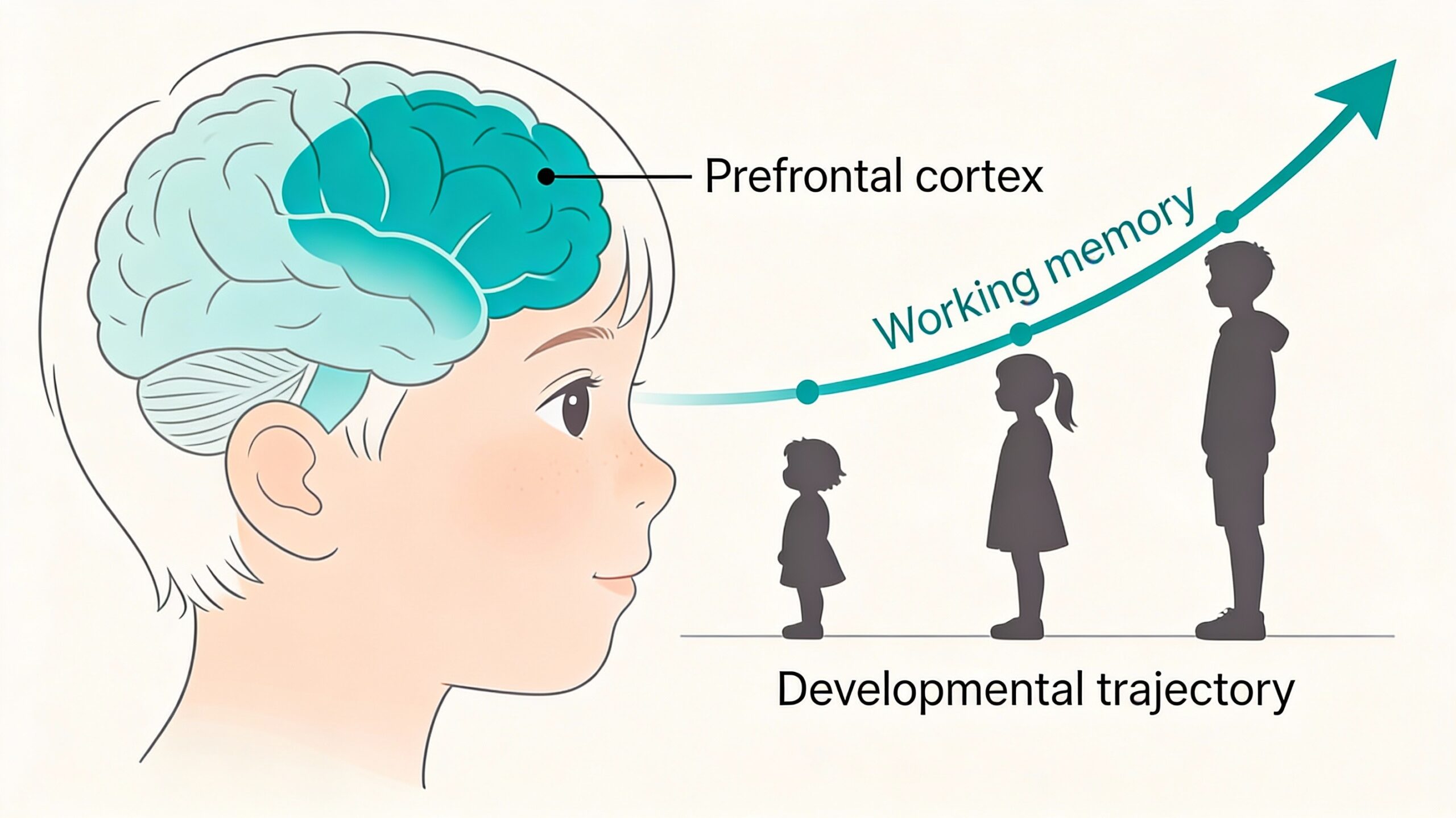

The cognitive abilities that enable a child to resist grabbing a forbidden sweet, to follow a teacher’s multi-step instruction, or to mentally rearrange the pieces of a puzzle are not mere products of simple learning. They are the outward manifestations of a profound neurodevelopmental process centred on the maturation of the brain’s prefrontal cortex (PFC) and its circuits. Working memory—the mental workspace for holding and manipulating information—serves as a foundational component of a suite of higher-order capacities known as executive functions. This article charts the neural trajectory of working memory development throughout childhood and adolescence, arguing that the protracted and experience-dependent sculpting of the PFC is the central mechanism underlying the emergence of the brain’s executive control system.

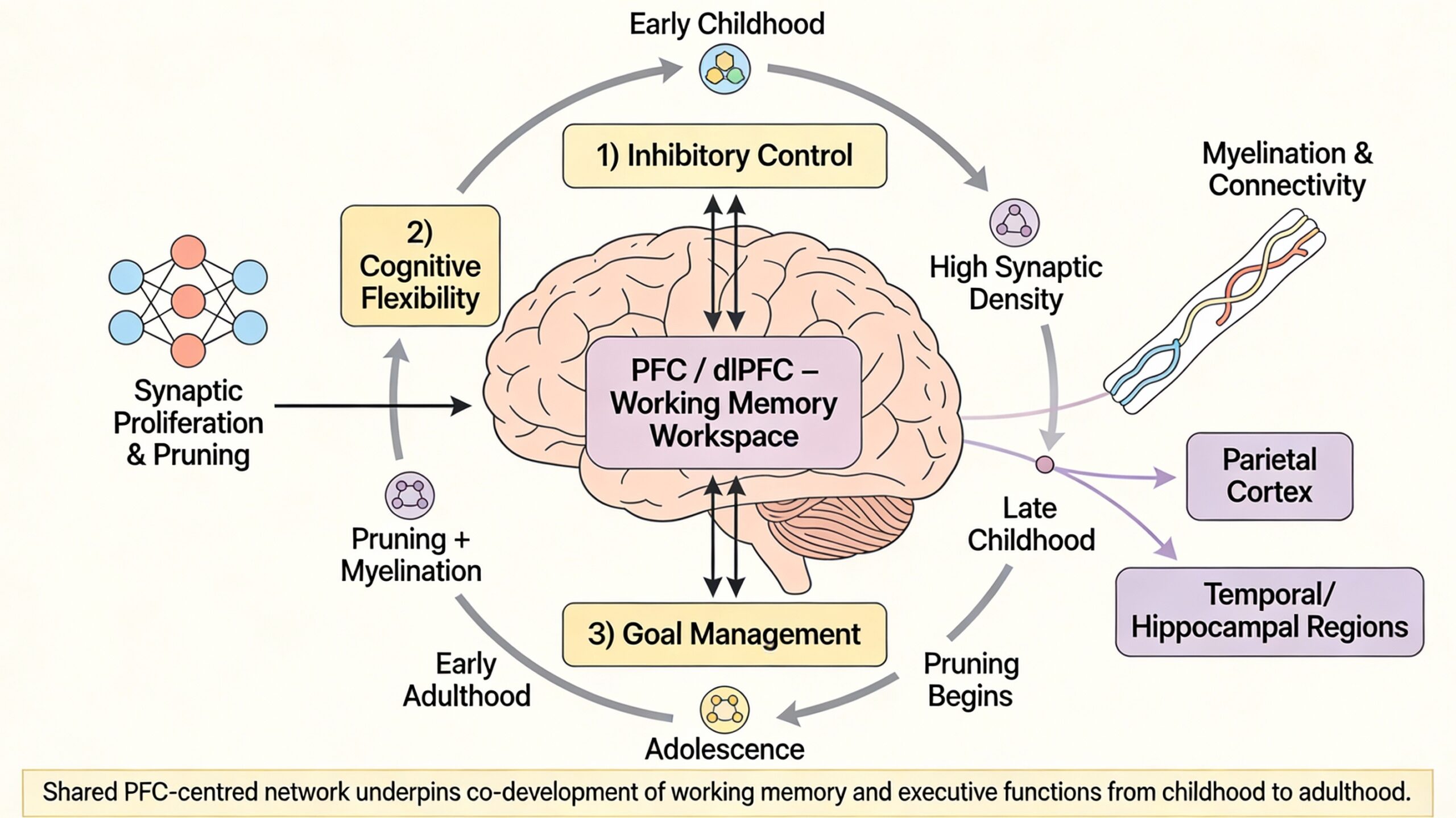

The Interdependent Architecture of Working Memory and Executive Function

The theoretical link between working memory and executive function is intimate and often recursive. Executive functions (EFs) are broadly defined as top-down mental processes required for conscious, goal-directed behaviour, with core components including inhibitory control, cognitive flexibility, and working memory itself (Diamond, 2013). This taxonomy, however, belies a deeply integrated system. Working memory is not merely a subcomponent; it is the essential cognitive workspace upon which other EFs operate. One cannot inhibit a distracting thought without holding the primary goal in mind, nor switch cognitive sets without maintaining the rules for both tasks. This functional interdependence is rooted in shared neural architecture. According to Miller and Cohen’s (2001) influential integrative theory, the PFC maintains patterns of activity that represent goals and the means to achieve them, biasing processing in more posterior brain systems. This top-down control relies fundamentally on the active maintenance and manipulation capabilities of working memory circuits within the PFC itself, particularly the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (dlPFC), and its dense connections to parietal and temporal association cortices (Fuster, 2015). Thus, the development of this PFC-centred network directly dictates the maturation of both working memory capacity and broader executive control.

The Protracted Behavioural Trajectory from Childhood to Adulthood

The developmental trajectory of these abilities is non-linear and strikingly prolonged, mirroring the slow maturation of its underlying neural substrate. Behavioural studies consistently show a steep improvement in working memory capacity, typically measured by span tasks, and complex executive task performance from early childhood through to adolescence. Research by Gathercole, Pickering, Ambridge, and Wearing (2004) demonstrated that the basic structure of working memory—comprising central executive, phonological loop, and visuospatial sketchpad components—is present from early childhood, but each component shows marked increases in capacity and efficiency with age. Performance on more demanding tasks, such as those requiring concurrent storage and processing (e.g., listening span) or strategic manipulation, shows even more protracted development. Longitudinal and cross-sectional studies indicate that while simple maintenance shows significant gains until mid-adolescence, the strategic and controlled aspects of working memory, crucial for complex reasoning, may not reach adult levels until the early twenties (Luna, Marek, Larsen, Tervo-Clemmens, & Chahal, 2015). This extended behavioural curve is not a simple function of knowledge acquisition; it is a direct reflection of the underlying structural and functional neural maturation of the frontoparietal network.

Structural Maturation: Synaptic Sculpting and Myelination

The PFC is one of the last brain regions to reach full structural maturity, characterised by two simultaneous, complementary biological processes: synaptic proliferation and pruning, and increased white matter myelination. During early childhood, the PFC exhibits an overabundance of synaptic connections, a state of exuberant connectivity that provides the neural substrate for immense learning potential (Huttenlocher & Dabholkar, 1997). However, cognitive efficiency at this stage is low due to “neural noise” and poor signal differentiation. From late childhood through adolescence, experience guides a protracted process of synaptic pruning, where frequently used connections are strengthened and unused ones are eliminated, leading to more refined and efficient neural circuits (Tau & Peterson, 2010). Concurrently, there is a significant increase in myelination within the PFC and along the major fibre tracts connecting it to other regions, such as the superior longitudinal fasciculus linking frontal and parietal cortices. This myelination, which continues into the third decade of life, enhances the speed and reliability of neural transmission, allowing for faster integration of information across distributed networks (Lebel, Treit, & Beaulieu, 2019). This dual process of pruning and myelination fundamentally refines the brain’s hardware, transforming a diffuse, noisy network into a streamlined and efficient one.

Functional Specialisation and Network Integration

Complementing these structural changes are profound shifts in functional brain activity and connectivity. Neuroimaging evidence reveals a developmental progression from diffuse to focal recruitment of prefrontal regions. Functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) studies show that young children often activate broader, more diffuse areas of the PFC during simple working memory tasks compared to older children and adults, who show more focal and robust activation in specialised regions like the dlPFC (Durston et al., 2006). This reflects a transition from a less efficient, effortful system to a more specialised and automatised one. Furthermore, there is a critical shift towards increased functional integration. Research by Finn et al. (2010) demonstrated that while children show strong functional connectivity within local brain regions, adolescents and adults exhibit stronger long-range connectivity between the PFC and other critical areas, such as the parietal cortex (for spatial attention and storage) and the hippocampus (for long-term memory integration). This enhanced network integration, often termed the shift from a “local to distributed” organisation, allows for the seamless coordination of maintenance, manipulation, and retrieval processes that define mature working memory. Effective connectivity analyses suggest that the PFC’s role evolves from being merely co-activated with other regions to exerting more sophisticated top-down control over them (Marek, Hwang, Foran, Hallquist, & Luna, 2015).

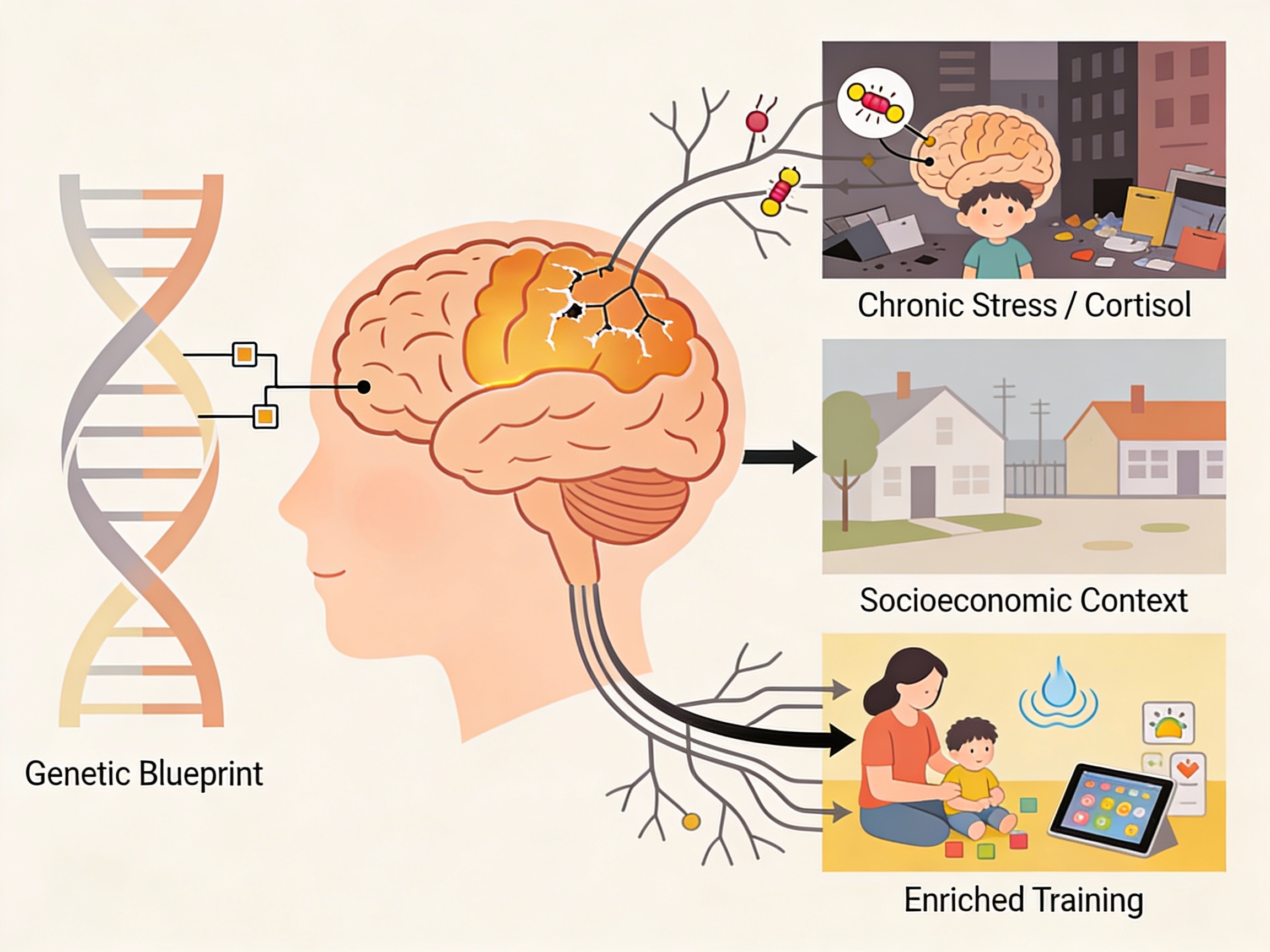

The Dynamic Interplay of Genes and Environment

This neural maturation is not a predetermined, isolated process. It is profoundly shaped by a dynamic and continuous interplay between genetic blueprint and environmental experience. Quantitative genetic studies indicate a substantial heritable component to the structure and function of PFC circuits, with genetic factors accounting for a significant portion of individual differences in working memory performance (Friedman et al., 2008). However, this genetic expression is modulated by experience. For example, chronic stress and socioeconomic disadvantage are associated with altered prefrontal development and poorer executive function outcomes. The mechanism is believed to involve the dysregulation of stress hormones like cortisol, which, in high and chronic levels, can impair PFC synaptic architecture and function, particularly in the highly plastic period of childhood (Lupien, McEwen, Gunnar, & Heim, 2009). Conversely, enriched environments, responsive, scaffolded caregiving, and targeted cognitive training can foster stronger executive skills. Interventions such as those involving structured play, mindfulness, or computerised training are thought to work by providing repeated, graded challenges to the PFC system, thereby promoting healthy synaptic strengthening, pruning, and network specialisation (Diamond & Lee, 2011). This evidence underscores that the developing PFC is an “experience-expectant” organ, designed to be sculpted by interaction with the world.

In conclusion, the development of working memory is a cardinal feature of cognitive maturation, orchestrated by the slow and experience-dependent sculpting of the prefrontal cortex. The journey from the diffuse, effortful activation of early childhood to the focal, efficient, and well-integrated networks of adulthood encapsulates the neural basis of becoming an effective “executive” of one’s own mind. This map of neural trajectory reveals working memory not as a static cognitive box but as a dynamic, developing system at the heart of executive control. Understanding this trajectory is not merely an academic exercise; it provides a crucial framework for identifying sensitive periods of heightened neuroplasticity, for crafting biologically informed interventions for neurodevelopmental disorders like ADHD, and for structuring educational and social environments that optimally support the growth of these foundational cognitive capacities. The childhood executive is not born, but built—neuron by neuron, connection by connection, through the continuous dialogue between an evolving biological architecture and a shaping environment.

References

Diamond, A. (2013). Executive functions. Annual Review of Psychology, 64, 135–168.

Diamond, A., & Lee, K. (2011). Interventions shown to aid executive function development in children 4 to 12 years old. Science, 333(6045), 959–964.

Durston, S., Davidson, M. C., Tottenham, N., Galvan, A., Spicer, J., Fossella, J. A., & Casey, B. J. (2006). A shift from diffuse to focal cortical activity with development. Developmental Science, 9(1), 1–8.

Finn, A. S., Sheridan, M. A., Kam, C. L. H., Hinshaw, S., & D’Esposito, M. (2010). Longitudinal evidence for functional specialization of the neural circuit supporting working memory in the human brain. Journal of Neuroscience, 30(33), 11062–11067.

Friedman, N. P., Miyake, A., Young, S. E., DeFries, J. C., Corley, R. P., & Hewitt, J. K. (2008). Individual differences in executive functions are almost entirely genetic in origin. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 137(2), 201–225.

Fuster, J. M. (2015). The prefrontal cortex (5th ed.). Academic Press.

Gathercole, S. E., Pickering, S. J., Ambridge, B., & Wearing, H. (2004). The structure of working memory from 4 to 15 years of age. Developmental Psychology, 40(2), 177–190.

Huttenlocher, P. R., & Dabholkar, A. S. (1997). Regional differences in synaptogenesis in human cerebral cortex. The Journal of Comparative Neurology, 387(2), 167–178.

Lebel, C., Treit, S., & Beaulieu, C. (2019). A review of diffusion MRI of typical white matter development from early childhood to young adulthood. NMR in Biomedicine, 32(4), e3778.

Luna, B., Marek, S., Larsen, B., Tervo-Clemmens, B., & Chahal, R. (2015). An integrative model of the maturation of cognitive control. Annual Review of Neuroscience, 38, 151–170.

Lupien, S. J., McEwen, B. S., Gunnar, M. R., & Heim, C. (2009). Effects of stress throughout the lifespan on the brain, behaviour and cognition. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 10(6), 434–445.

Marek, S., Hwang, K., Foran, W., Hallquist, M. N., & Luna, B. (2015). The contribution of network organization and integration to the development of cognitive control. PLOS Biology, 13(12), e1002328.

Miller, E. K., & Cohen, J. D. (2001). An integrative theory of prefrontal cortex function. Annual Review of Neuroscience, 24, 167–202.

Tau, G. Z., & Peterson, B. S. (2010). Normal development of brain circuits. Neuropsychopharmacology, 35(1), 147–168.